- Stagflation risks have emerged as a cause of extraordinary high volatility in FX markets this year

- We deconstruct how changes in rates, inflation expectations, and volatilities affect G10 currencies

- GBP and JPY suffered more from higher inflation volatility and lower short-term rate differentials

- USD was a beneficiary given higher short-term interest rates and higher rates volatility

- When stagflation risks abate, it may finally allow a reversal in currency performance

Taking stock of FX volatility spikes

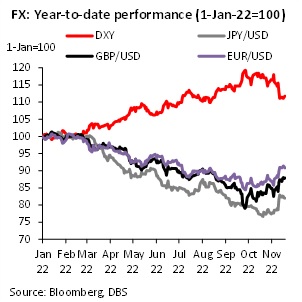

Elevated inflation and idiosyncratic uncertainties around pandemic, war, and political economy have contributed to extreme currency market volatility this year. The USD gave an extraordinarily strong performance, with the DXY gaining as much as 19%. But others such as the JPY, GBP, and EUR posted sharp declines.

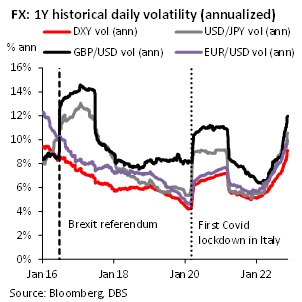

Such large USD shifts and an accompanying rise in volatility reflect wider uncertainty about rates and inflation, as markets fret about rising price pressures amid a global slowdown, signifying a rare return of stagflation risks. Realized volatilities for DXY, USD/JPY, GBP/USD and EUR/USD have all surged this year towards highs that were associated with acute market stresses in the past.

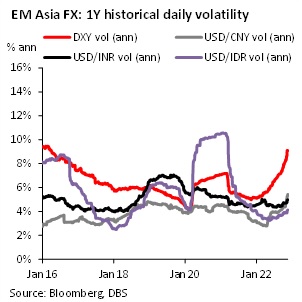

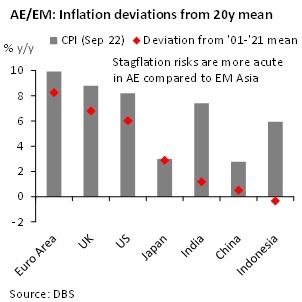

In contrast to advanced economies (AE), EM Asia’s realized FX volatilities are subdued. Asian currencies have shown greater resilience despite sharp USD strength. Despite their selloffs, CNY, INR, and IDR volatilities still hover near their 2021 lows. Such stability can be partially attributable to more stable inflation, which have not overly deviated from historical norms unlike inflation across AEs. We drill further into examining how shifts in inflation and rates (as well as their degree of uncertainty) impact currencies, so as to better position portfolios amid higher than usual macro uncertainty.

Exchange rate models: Theory and pitfalls

Since the 1970s, there has been a large body of work on exchange rate determination. Messe and Rogoff (1983) found that it is difficult for exchange rate model forecasts to beat a random walk model. This was true across a range of models utilizing theory-based factors, including (i) money supply, (ii) real incomes, (iii) short-term interest rates, (iii) long-run inflation expectations and (iv) cumulated trade balances. Additional research by Messe and Rogoff (1988), as well as Campbell and Clarida (1987), also found limited evidence of links between real exchange rates and real interest rate differentials.

However, Baxter (1994) argued that the relationship between exchange rates and interest rates is stronger across low frequencies, and this is not evinced when analysing monthly differences of real exchange rates, which had filtered out information in levels. Engel and West (2005) proposed that the inherent difficulty in tying currencies to macro fundamentals arises from the fact that any non-stationary fundamental will result in near-random walk behaviour for currencies.

Thus, there is a need for careful treatment of inherent non-stationarity in real exchange rates. We believe our DEER valuations provide a practicable way to resolve this issue. The DEER incorporates the effect of productivity and terms of trade differentials on exchange rates, and its valuations can be considered as a stationary series with no loss of information relating to real exchange rate levels (see Chang (2020) for details).

The long and short of rates

Interest rate markets hold idiosyncrasies arising from institutional differences between advanced economies (AE) with deep and liquid debt markets, and emerging market (EM) economies with shallower debt markets, and with varying degrees of capital controls. A rise in rates for an EM economy tends to have a different meaning compared to the norm.

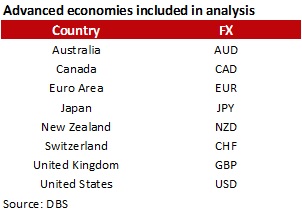

For this reason, we restrict our real exchange rate (proxied by the DEER) analysis to only a subset of eight AEs with well-developed debt markets, high international capital mobility, credible monetary authorities, strong institutions, and high political stability. The 8 economies and currencies are as below:

We make a distinction between short-term and long-term rates, as they relate to different segments of the market, with perhaps different FX impact. Both the 1Y FX-swap implied rate and the 10Y government bond yield are used as proxies for short-term and long-term rates. For simplicity, we take rate differentials against a mean for all 8 advanced economies, as there are unlikely to be substantive differences relative to a trade-weighted rate differential.

We estimate sensitivities of the real exchange rate (DEER) against both short and long-term rate differentials via a fixed effects panel regression, using quarterly data from Q1 2000 to Q3 2022.

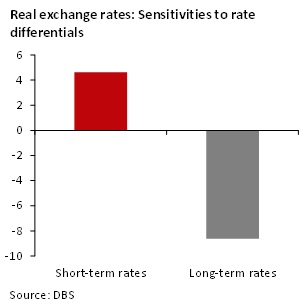

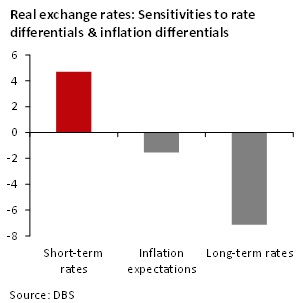

We found that short-term and long-term rate differentials have quite different impact on real exchange rates directionally. For short-term rates, our results are aligned with empirical studies by Fama (1984) and others documenting the forward premium anomaly, namely that a currency tends to appreciate when its nominal rates exceed foreign rates.

But the real exchange rate shows a negative relationship with long-term rates differentials. We see a couple of reasons for this. First, long-term rates contain both a real rate and an inflation expectations component. If the rise in long-term rates reflect an increase in inflation expectations more than an increase in the real rate, then this could correspond to a weaker currency. Second, a rise in economic uncertainty may contribute to a simultaneous rise in long-end rates and a fall in the currency. The sell-off of both GBP and gilts post the UK’s mini budget in October is one example. Indeed, under a scenario of stagflation, both inflation expectations and economic uncertainty should change meaningfully, driving currencies too.

Quantifying expectations and uncertainty

As such, we expand our real exchange rate sensitivity analysis to jointly include 1/ inflation expectations, and 2/ economic risk or uncertainty, which in our case is proxied by the volatility of both inflation expectations and rates. Unlike interest rates, inflation expectations and volatility are not always expressed in markets with sufficient number of observations. Hence, we develop 24 country models of the conditional expectations of inflation, short-term rate volatility, and long-term rate volatility to obtain estimates for our analysis.

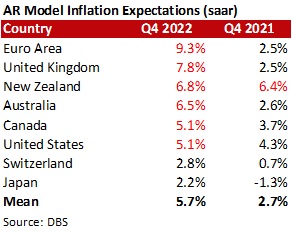

With regards to inflation expectations, we focus only on short-term expectations. This can be inferred from an adaptive model, where conditional inflation expectations or forecasts are predicated on past inflation outcomes.

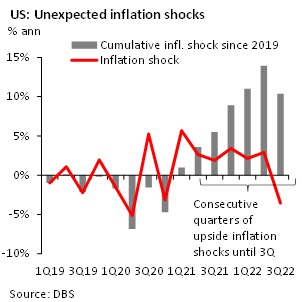

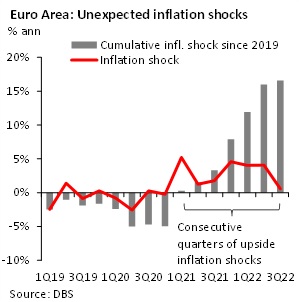

Deviations from inflation expectations can be interpreted as an unexpected change, or shock. Starting Q1 2021, inflation shocks across the US and many other economies have surprised persistently to the upside (though shocks have abated somewhat in Q3). While they are partially caused by idiosyncratic developments, sustained shocks invariably shift short-term inflation expectations upwards. Thus, our models show a dramatic upshift in inflation forecasts for Q4 compared to a year ago. The Euro Area, UK, Australia, New Zealand, United States and Canada all have conditional inflation forecasts of well over 5% (q/q annualised).

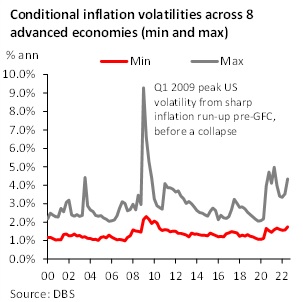

The consequence of persistent upside inflation shocks is rising economic uncertainty, with regards to both future inflation as well as interest rates. Such uncertainty may be proxied by the conditional volatility of inflation and interest rates, which can be modelled via a Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (or GARCH) model as suggested by Bollerslev (1986). Conditional heteroskedasticity means that volatility can be subject to change over time, depending on the magnitude of previous shocks as well as the conditional volatilities of previous periods.

Our models show that conditional inflation volatilities have risen sharply since 2020, after a long period of stability since 2012. There is also significant variation in magnitude from 1.7% (lower uncertainty) for Switzerland to 4.3% (higher uncertainty) for the UK. Minimum and maximum values of conditional inflation volatilities have also diverged by the most since the 08/09 GFC, possibly exerting an uneven impact on exchange rates.

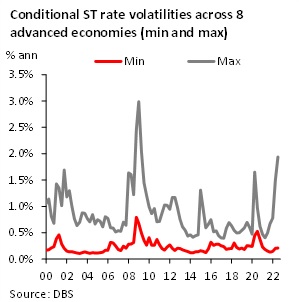

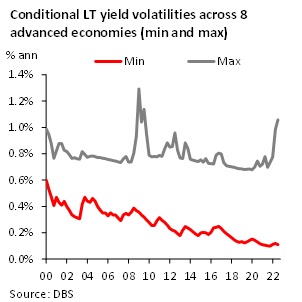

GARCH models can similarly be applied to conditional volatilities of short-term and long-term rates. Following Longstaff and Schwartz (1992), we model monthly rates with a GARCH (1,1) model, assuming that the mean change in rates is zero. Our monthly conditional rates volatility is then consolidated into quarterly volatility. We found that our estimates are fairly comparable to swaption-implied volatilities, where these are traded and available.

As with inflation volatilities, short-term rate volatilities have spiked this year, primarily due to upsized rate hikes by the Fed and other central banks. There is also a widening divergence across countries, from 0.2% (ann.) in Japan to 1.9% in Australia. We found that the gap between minimum and maximum values of short-term rate volatilities is also at its widest since 08/09.

Divergence across long-term rate volatilities is equally stark, ranging from 0.1% (ann.) in Japan to 1.1% in Australia. Given such disparate swings in rate volatilities across countries, their impact on currencies could be more consequential than usual.

Modelling the impact of rates, inflation expectations and volatility jointly

After quantifying inflation expectations and rates volatility, we expand our earlier regression analysis using these additional conditional variables. We draw conclusions with regards to the sensitivities of the real exchange rate to each factor below:

1/ Higher short-term rate differentials are a positive driver for the real exchange rate. Interestingly, sensitivity of the short-term rate differential is larger than that for inflation expectations, suggesting that nominal rates are perhaps more influential than real rates.

2/ Real exchange rates are still inversely related to long-term rate differentials. Care is needed when studying the correlation of 10y yield differentials with currencies, as a seemingly positive relationship may not hold up after factoring the impact of short-term rates.

3/ Real exchange rates react negatively to a rise in inflation expectations. Even though inflation differentials are already factored in real exchange rates, an additional negative impact on currencies could still register via the inflation expectations channel.

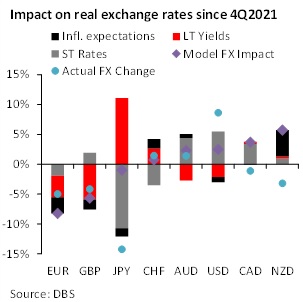

Collating these sensitivities, we can model the expected impact for all 8 currencies amid the sharp divergence of rates and inflation expectations. We compare our modelled expected impact for the real exchange rate against the actual change for the first three quarters of 2022:

Our model expectations were aligned with the direction of change for 6 out of 8 real exchanges rates. Both EUR and GBP real exchange rates are expected to depreciate by more than 5% given higher short-term inflation expectations, on top of higher long-term yields. Indeed, EUR and GBP had under-performed to a comparable magnitude. Meanwhile, Japan’s short-term rate differentials imply a sizeable negative impact for the JPY, though the model’s net FX impact after factoring in lower long-term rates is small.

On the other end, USD, AUD, and CAD stand out as benefitting from higher short-term rate differentials. Both USD and AUD had shown real appreciation in line with model estimates, but the CAD underperformed our model’s forecast.

Next, we factor in currencies’ sensitivities to shifts in the volatilities of both interest rates and inflation expectations.

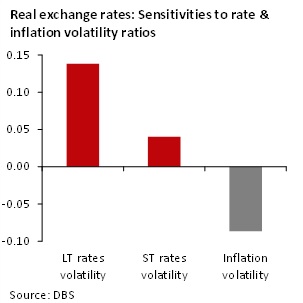

4/ Surprisingly, we found that real exchange rates are positively influenced by a rise in the conditional volatility of long-term rates.

5/ Real exchange rates are also positively influenced by a rise in the conditional volatility of short-term rates, albeit to a smaller extent. Reasons for the positive currency impact of higher rates volatility are beyond the scope of our analysis, though we shall allude to some specific cases related to central bank policy.

6/ Real exchange rate are negatively impacted by higher inflation volatility, underscoring the importance of low and stable inflation for currency stability.

Given that inflation volatilities are typically twice to thrice as large as rate volatilities, while currencies’ sensitivities to both are comparable in magnitude, it is reasonable to expect that stagflation poses greater downside risks for currencies, simply because of the larger magnitude of inflation volatility. But our results also imply an avenue to buffer against such downside: upsized policy rate hikes that trigger a surge in both short-term and long-term rates volatility. Their positive impact on currencies could come from warding off shorts through a calibrated widening of policy uncertainty.

In context of this, Japan’s commitment to yield curve control may be a double-edged sword. Providing stable economic support by capping yields involves a trade-off for currency strength. Perhaps policy-suppressed yield volatility is perceived as having an implicit negative skew risk for bond investors, which could explain why extremely low JGB yield volatility produces a negative impact on the JPY.

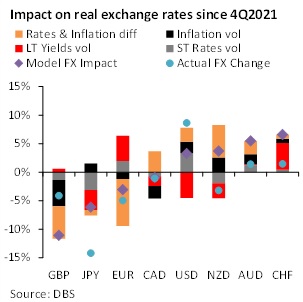

After including the impact from inflation and rates volatilities, directional changes for 7 out of 8 currencies can be explained by our model. It is a striking result that underscores how much stagflation-linked risks have driven currencies this year. NZD is the only one that depreciated against our model expectation—not entirely surprising given its richer DEER valuation.

Our model expects GBP to be the worst performer with a loss of 11.1%, weighed by factors from higher inflation volatility to higher long-term bond yields. The JPY ranks second with an expected loss of 6.2%, dragged by lower-than-norm volatility for long-end rates. Still, the JPY loss has well overshot our model expectations, implying scope for the JPY to outperform.

Among the expected outperformers based on our model estimates, CHF ranks the best with an expected gain of 6.6%, due primarily to rising long-term rate volatility. The USD is also expected to strengthen, but by a more middling 3.3%. Its gain is attributable to factors such as a lower relative inflation volatility, and a surge in short-term rates level and volatility, driven by the Fed’s accelerated rate hikes. However, actual gain for the USD has significantly overshot our model’s expected gain.

FX reversals hinge on easing stagflation fears

Our analysis made clear the exchange rate impact from factors related to stagflation risks, namely (i) nominal rates and inflation expectations, and (ii) their respective volatilities. Sharp changes in rates and inflation expectations presented unexpected risks and challenges for currency investment this year. In hindsight, our DEER strategy’s underperformance this year is attributable to these factors (see DEER Recommendations, 4 Nov 22), with GBP and JPY longs and USD shorts being more adversely affected by such factors.

When stagflation risks fade, FX volatility due to these factors are likely to ease. Policymakers are already acting forcefully to temper risks of accelerating inflation. The USD also looks overstretched compared to model estimates, while impetus from Fed rate hikes could ease. Diminished stagflation risks may finally allow currencies to reverse and misalignments to narrow, particularly for those most stretched compared to their valuations.

Chang Wei Liang

To read the full report, click here to Download the PDF.

Topic

The information herein is published by DBS Bank Ltd and/or DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited (each and/or collectively, the “Company”). This report is intended for “Accredited Investors” and “Institutional Investors” (defined under the Financial Advisers Act and Securities and Futures Act of Singapore, and their subsidiary legislation), as well as “Professional Investors” (defined under the Securities and Futures Ordinance of Hong Kong) only. It is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the Company does not make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy, completeness, timeliness or correctness for any particular purpose. Opinions expressed are subject to change without notice. This research is prepared for general circulation. Any recommendation contained herein does not have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation and the particular needs of any specific addressee. The information herein is published for the information of addressees only and is not to be taken in substitution for the exercise of judgement by addressees, who should obtain separate legal or financial advice. The Company, or any of its related companies or any individuals connected with the group accepts no liability for any direct, special, indirect, consequential, incidental damages or any other loss or damages of any kind arising from any use of the information herein (including any error, omission or misstatement herein, negligent or otherwise) or further communication thereof, even if the Company or any other person has been advised of the possibility thereof. The information herein is not to be construed as an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to provide any investment advice or services. The Company and its associates, their directors, officers and/or employees may have positions or other interests in, and may effect transactions in securities mentioned herein and may also perform or seek to perform broking, investment banking and other banking or financial services for these companies. The information herein is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country, or other jurisdiction (including but not limited to citizens or residents of the United States of America) where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The information is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security in any jurisdiction (including but not limited to the United States of America) where such an offer or solicitation would be contrary to law or regulation.

This report is distributed in Singapore by DBS Bank Ltd (Company Regn. No. 196800306E) which is Exempt Financial Advisers as defined in the Financial Advisers Act and regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. DBS Bank Ltd may distribute reports produced by its respective foreign entities, affiliates or other foreign research houses pursuant to an arrangement under Regulation 32C of the Financial Advisers Regulations. Singapore recipients should contact DBS Bank Ltd at 65-6878-8888 for matters arising from, or in connection with the report.

DBS Bank Ltd., 12 Marina Boulevard, Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3, Singapore 018982. Tel: 65-6878-8888. Company Registration No. 196800306E.

DBS Bank Ltd., Hong Kong Branch, a company incorporated in Singapore with limited liability. 18th Floor, The Center, 99 Queen’s Road Central, Central, Hong Kong SAR.

DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited, a company incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability. 13th Floor One Island East, 18 Westlands Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong SAR

Virtual currencies are highly speculative digital "virtual commodities", and are not currencies. It is not a financial product approved by the Taiwan Financial Supervisory Commission, and the safeguards of the existing investor protection regime does not apply. The prices of virtual currencies may fluctuate greatly, and the investment risk is high. Before engaging in such transactions, the investor should carefully assess the risks, and seek its own independent advice.