In the capital markets, Covid-induced concerns have nudged ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors to take centre stage in investment decisions. PHOTO: PEXELS.COM

SUSTAINABLE assets in Asia hit new highs in the second quarter of this year, a testament that environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investments are still on-trend.

Total assets invested in Asia-domiciled funds stood at a record US$36.3 billion at the end of June, up 3.3 per cent from the last quarter, Morningstar data from July showed.

That said, quarterly flows slowed with fewer new fund launches. The breather gives investors a chance, perhaps, to look more closely at what they are putting money into.

One material risk behind the rising number of ESG funds is greenwashing, which Fidelity calls giving investments a "green sheen". The risk here is that financial players are adding an ESG label to investments simply because the theme is in vogue.

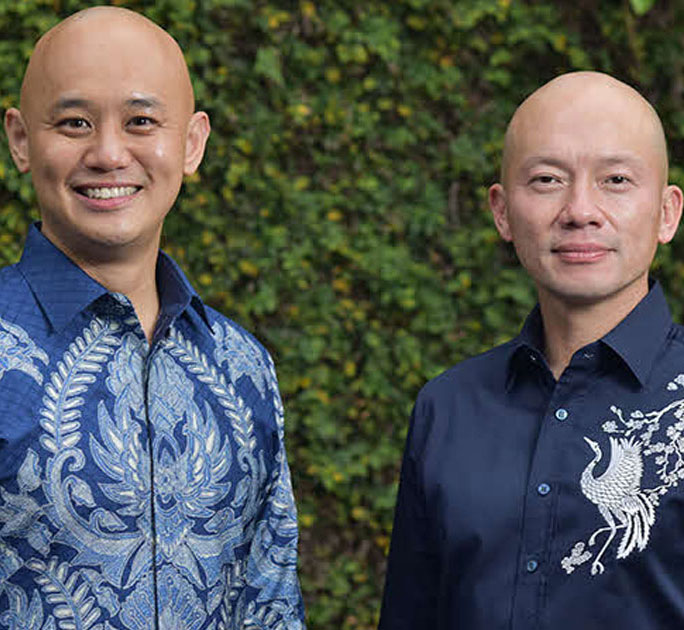

John Ng, head of funds selection and advisory, DBS Private Bank, defines greenwashing as a misrepresentation that tries to capitalise on the increasing interest in sustainable products or services.

Greenwashing is a form of misleading marketing where a company or its products and services are repackaged and presented as "better" with respect to climate change, the environment, or society, without proper documentation to back this claim.

- Greenwashing firms may withhold the full reality of their credentials on environment or sustainability. Companies are usually transparent about third-party certification because these certifications are usually expensive and take a long time to achieve.

- Hypothetical examples of greenwashing include: an apparel company claiming that its products are "sustainable" when the materials contain only 5 per cent recycled polyester; or an energy company claiming to centre its development focus on renewable energy, yet choosing to promote energy based on fossil fuels in their investment decisions.

Research by the Singapore Management University (SMU) in July showed that some hedge funds may already be sending deceptive signs of their compliance to ESG standards.

Funds may be publicly signalling commitment to socially responsible investing by endorsing the United Nations' Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI). But in its study of hedge funds around the world, the SMU report finds that a "significant" number of hedge funds which endorse PRI (21 per cent) have inadequately low ESG exposure through their portfolio holdings.

These "greenwashing funds" subsequently underperform high-ESG signatories and non-signatory hedge funds in generating financial returns.

The problem is that these greenwashing funds have poor governance, weak incentive alignment, and greater operational risk, yet attract significantly more flows from asset owners than non-signatories do.

Walk the talk

"Given the unprecedented interest in responsible investment by asset owners, one concern is that some fund managers may deceptively endorse the PRI to attract flows from responsible investors while not honouring their promise of incorporating ESG into their investment decisions," the SMU report said.

These results "raise doubts as to whether these signatories are exemplars of responsible investment, and raises the need for investors to maintain scrutiny over their investments".

How do investors ensure that fund managers walk the talk?

DBS's Mr Ng said the bank assesses funds by looking at factors such as the fund manager's track record, the depth of focus on ESG and innovation, as well as sustainable competitive advantages that make them more likely to outperform their benchmarks.

The bank also assesses the degree to which fund managers are able to influence their underlying companies in board positions.

DBS is generally cautious when it comes to ESG-thematic funds with narrow investment coverage. "The more narrowly focused they are, the more we steer clear. Many of these are driven by concepts that are current 'hot' topics, but may not be sustainable investment ideas for the long term," said Mr Ng.

ESG-thematic funds with too narrow a scope may not provide much opportunity for active management against a relevant benchmark, since there may only be a few companies that fall within such a scope, he added. "For certain themes that are especially nascent, there may not even be an appropriate benchmark. The purity of the theme therefore comes into question: is it true to label?"

Checks and balances

The bank is supportive of those with a broader remit and that have the flexibility to adapt to changes in investment opportunities over time - giving these funds greater room for active management. DBS earlier told The Business Times that investing along ESG lines is meant as portfolio insurance against potential E, S, and G risks. Mr Ng said fund factsheets or marketing materials may not be enough for investors to distinguish which falls under "greenwashing".

The bank has integrated MSCI ESG Ratings into its product suite. In general, funds that carry BBB ratings and above can be considered to hold a higher level of ESG principles.

Still, a realistic challenge now is that there are varying ESG scoring methods in the market. A 2020 Milken Institute report looked at a sample of 943 firms' performance in 2018, the latest year for which all ESG scores from three major rating agencies - RobecoSAM, Sustainalytics, and Thomson Reuters - were available. The analysis showed that the three rating agencies give very different ESG scores, with a correlation below 0.5, to more than 60 per cent of the firms.

The exception is for the worst-performing ones. There, the rating agencies were in agreement - so shown by the correlation of 0.95 or more - for only 10 per cent of the firms that made the bottom of the list when it came to ESG standards.

"To a certain extent, the availability of ratings with different definitions is natural, given the subjective nature of ESG criteria," the Milken report said. "But more importantly, it might be required to satisfy investors and asset managers with different needs and motivations."

The report said that while agencies do not have to agree on a single definition, they should focus on standardising data, labelling ratings more clearly. They should also be transparent about their objectives. "Such priorities would allow market participants to differentiate products better and to determine whether a particular definition aligns with their goals," it noted.

This article was written by Jamie Lee and first published in The Business Times on 11 Aug 2021.