The industry needs time to work through issues and find its footing, to support the decarbonisation of the economy

Corporations, fund managers and financial institutions are feeling the heat – not just from climate change, but also from financial regulators who are cracking down on greenwashing.

Although investors have long shown some scepticism when it comes to the reporting of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, greenwashing allegations have been in sharp focus since German police raided the offices of asset manager DWS, which is majority-owned by Deutsche Bank, 3 months ago.

Financial watchdogs are piling on the pressure as they pledge to scrutinise fund managers on whether their ESG funds are what they claim to be, whether disclosures from corporations are in line with their business practices, and whether the parameters ratings agencies use to make sustainability assessments are suitable.

The term ‘greenwashing’ emerged in the 1980s, and was first coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld to refer to the corporate practice of making misleading claims on their sustainability efforts.

Forty years later, the waters are even muddier as the finance sector begins looking at environmental goals from an investing lens.

The ESG investing space has ballooned in the last 2 years, accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic. According to financial services company Morningstar, total worldwide sustainable assets in 2021 stood at US$2.7 trillion across more than 5,900 funds.

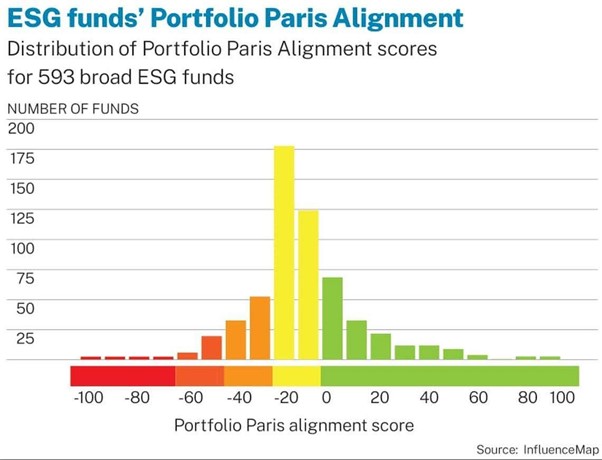

In an August 2021 report, however, InfluenceMap found that 71 per cent of 593 equity funds had a negative Portfolio Paris Alignment score, which is an indicator the climate think tank came up with to assess the alignments between the forecasted real-economy activities owned by the portfolio through its shareholdings and the Paris Agreement on climate change.

A month before that, the International Organization of Securities Commissions found little clarity, alignment or transparency in methodologies for rating of ESG funds. It also noted potential conflict of interest where consulting companies provided ESG services to companies but also produced ratings or data products incorporating the same companies.

While some in the market may have deliberately sought to exaggerate their sustainability claims, other greenwashing allegations could have arisen because of differing ideas of what sustainability means: How are the fund constituents having an ESG policy assessed? What if the fund has a strong holding of banks that finance both renewable energy solutions, and oil and gas companies that have transition plans?

Greenwashing is therefore partly attributable to the lack of clear definitions of ESG investing. There is a wide variety of methodologies and approaches to ESG investing in the market.

And although the evolution of the ESG space in such a short span of time does signal innovation in the market, the greater the variety of ESG investments, the higher the risk of greenwashing.

Jon Hale, director of ESG research for the Americas at MorningStar, said real-world sustainable investment strategies and funds often combine multiple approaches.

One approach is to integrate ESG tools and scores to improve the investment analysis of one’s portfolio, such as potential risks from higher carbon prices. Such an investing approach, however, may not necessarily generate impact.

Even among ESG products that profess to have an impact, meanwhile, some have a focus on biodiversity, while others might focus on decarbonisation.

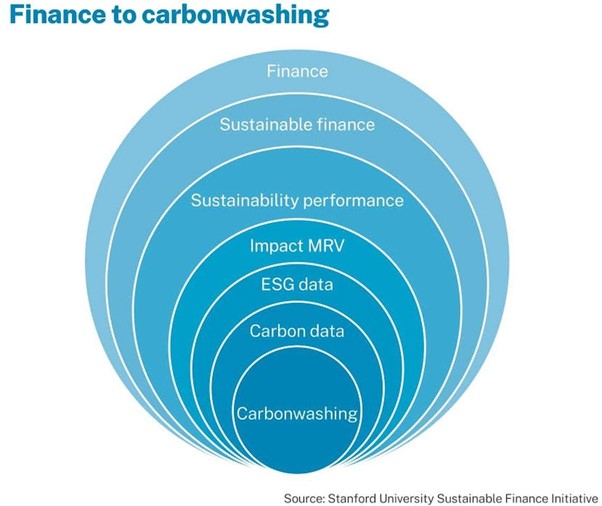

Complicating the picture even more is a new trend called carbonwashing, coined by Soh Young In and Kim Schumacher – researchers from Stanford University’s Sustainable Finance Initiative.

The term captures the specific focus of many corporates on reducing carbon emissions to net zero.

Regulators’ impact limited

Solar energy is undoubtedly the most affordable source of renewable energy. The business model is well-established, the solution can be deployed quickly, and there is a lot of capital available, said Pascual.

Using data from IEA, global asset manager BlackRock said that solar costs have declined by 85 per cent since 2010.

The Asia-Pacific region is already the global powerhouse for renewable energy, representing over 50 per cent of installed capacity and more based on forecasts, based on figures from investment data company Preqin.

Besides investing in energy infrastructure, Pascual pointed out that one often-overlooked method to reduce carbon emissions is simply to improve energy efficiency.

This includes switching to light-emitting diodes in residential and commercial buildings, deploying energy efficient air-conditioners and chillers, as well as using district-cooling technologies, said Mhaisalkar.

New opportunities

The consequences of greenwashing or carbonwashing are clear. Misleading claims can lead to a misallocation of capital. Money intended for sustainable purposes is directed to ones that are not, leaving less capital to fund solutions that can have a positive impact.

From an investor’s perspective, allowing greenwashing can be likened to failure of consumer protection, as investments are not going where they are advertised.

Regulators therefore need to up their game by coming up with improved sustainability reporting requirements that enhance data quality, availability and transparency.

The European Union has launched new rules on corporate sustainability reporting, which include detailed reporting on issues such as environmental rights, social rights, human rights and governance factors. They are also looking to come up with stricter parameters for ratings agencies that measure the ESG performance of companies.

In Singapore, the Monetary Authority of Singapore has mandated that fund managers disclose the investment strategies, metrics and criteria of retail funds sold with the ESG label. The Singapore Exchange, the city-state’s bourse operator, is also considering requiring all listed companies to prepare their sustainability reports using a common digital format.

Eyes are also on the International Sustainability Standards Board – a body under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation – to provide a global baseline of sustainability-related disclosure standards that could help investors and other capital market participants make informed decisions based on sustainability-related risks and opportunities of companies.

But although regulators can set standards and disclosure requirements, and enforce them, it is up to market players to respond.

Establishing standards takes time

Taking financial accounting as a comparison, accounting standards are taken for granted. Many forget that decades passed before this became a common practice among listed corporations.

Calls for international accounting standards began in the 1950s, and the International Accounting Standards Committee was set up in 1973. The committee is the predecessor of the International Accounting Standards Board, the other standards-setting body of the IFRS Foundation.

Despite its long history, market watchers say it fell short – especially in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009.

It may likewise take decades before sustainability reporting reaches a level of business-as-usual.

Unlike with financial accounting, though, the ecological clock is ticking on this.

A better analogy, perhaps, would be the many workplace accidents and deaths in industrialising economies in the late 1800s – which resulted in laws protecting workers, such as those on workplace safety and minimum wages. Instances of workplace abuse are, of course, still happening in this world – but have, for the most part, shifted from developed markets to economies with weaker enforcement capabilities.

Just as unions worked with industry to gradually change workplace practices, especially in the developed world today, credible and sustainable ESG investing could be accelerated by dedicated long-term stakeholders, steeped in sustainability expertise, stepping up to work with finance professionals to come up with workable standards.

Environmental activists have been very loud about their demands, but discussions on the development of green practices in ESG investing are still dominated by people trained in conventional finance.

Beyond withdrawing their funds, the recourse ESG investors have in the event of greenwashing is still limited.

It also remains to be seen whether ESG investors would make stronger demands, especially if their investments are meeting expected financial returns. Finding out that your investment funds went to a coal mining company instead of a solar panel manufacturer, for example, is very different from witnessing young girls fall to their death from a factory floor as they attempt to escape a raging fire engulfing the building – as in the case of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory incident in 1911.

Until sustainability reporting becomes business-as-usual, more greenwashing scandals are unavoidable. However, this does not mean we should throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Time and persistence will be crucial if ESG principles are to make a difference to decarbonisation of the economy. But history shows better standards are within reach.