Change has been slow, but opportunities to participate in the global decarbonisation movement are already emerging today

The science around climate change is well-documented.

An increase in climate hazards and risks to ecosystems and humans would be unavoidable if the global average temperature rise hits 1.5 degrees Celsius in the near term, said the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The Earth is currently heated to around 1.1 deg C above pre-industrial levels.

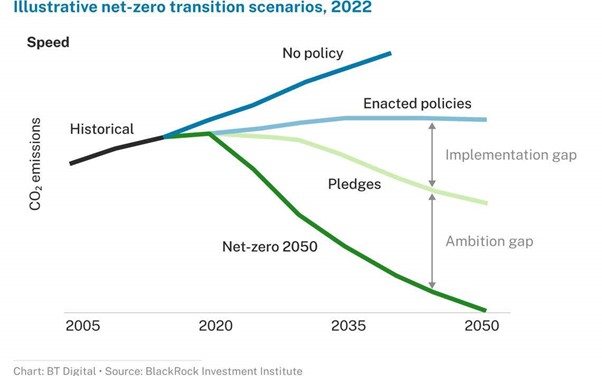

Amid a growing global movement rallying behind the need to limit warming to within 1.5 deg C, more governments and corporations are pledging to net-zero emissions, which simply means to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions to a level where the amount produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere are balanced.

But observers say change has been slow.

“This is a transformation challenge. We need to change all of our habits... We need (it to move at a) faster speed,” said Liew Wei Chee, Singapore managing partner of sustainability consultancy, ERM.

According to a recent report by the World Meteorological Organization, the probability of breaching that 1.5 deg C threshold is now higher than when the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015.

Asset manager BlackRock noted that there is an implementation gap between a government’s current policies and what it pledges, as well as an ambition gap between public commitments and the goals of the Paris Agreement.

To begin with, there is a wide variation among countries’ climate goals.

Out of the 128 countries that have made net-zero commitments, about 50 per cent have given themselves between 2041 and 2050 to do so, noted Fang Eu-Lin, sustainability and climate-change leader at professional services firm PwC Singapore.

“Within those pledges, the advancements of their implementation are also in different stages. Some are still in pledge, proposals and discussions, or in policy and law stages. Depending on the jurisdiction’s climate commitments and the state of implementation, this will have a significant influence on the real-economy decarbonisation on the ground,” she said.

Asia lags behind

Some regions are, admittedly, lagging behind others in their transition to a low-carbon economy. Asia-Pacific is home to 5 of the 10 largest carbon-emitting countries in the world, and that accounts for 45 per cent of global emissions.

Given that the region is home to many developing nations still in the early stages of economic developments and living standards, economic growth tends to take centre stage. This is partly why Asian companies tend to have lower environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings than their counterparts in Europe and North America, said DBS.

Complicating matters is the fact that countries in Asia face some of the greatest physical risks of climate change, said BlackRock.

“If Asia doesn’t get the transition right, the world doesn’t,” it said.

Within Asia, member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) have a “long way to go”, also because of the significant role coal still plays in the energy mix of many Asean economies, said Sean Lim, South-east Asia managing director and utilities lead at professional services company Accenture.

According to the Green Future Index, when it comes to building a low-carbon future, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia ranked in the bottom half of the list of 76 countries. In contrast, 15 of the top 20 countries were from Europe.

Asean’s energy demand, which has grown by more than 80 per cent since 2000 by doubling down on fossil-fuel use, is expected to contribute 12 per cent of the projected rise in global energy use in 2040, noted Suvro Sarkar, research analyst at DBS.

“Thus, balancing economic growth and energy security with decarbonisation goals will be a big challenge in the Asean region, and even Singapore will have its task cut out (for it), given its historical position as a hydrocarbon trading centre and lack of space in the island-state to accommodate renewable energy projects,” said Sarkar.

While Singapore has made significant progress in keeping its net-zero commitments – such as implementing a carbon tax and mandating that all vehicles be electric by 2040 – it ranks 27th out of 142 countries in terms of its emissions per capita, showed 2019 data from the International Energy Agency.

With about 8 tonnes of carbon dioxide emitted per capita, Liew noted that this figure is “quite high”, though he said that some products produced from carbon-intensive industries, such as the petrochemical sector, are not consumed in Singapore but are exported overseas.

Out of the total 51.6 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emitted in 2019, 45 per cent of it came from industry, 39 per cent from the power sector, and close to 14 per cent from transport.

High costs, figuring out how to implement decarbonisation solutions and leadership commitments to net zero are some factors inhibiting decarbonisation, said observers.

While the market may know of clean energy solutions such as renewable energy, Liew said the bigger question of how to deploy and implement them are some issues governments and corporations are grappling with.

He also pointed out that companies often need to justify capital expenditure on decarbonisation solutions.

BlackRock pointed out that the “green premium” needs to be lowered in order for net-zero emissions to be achievable, and that this will need funding, as well as a concerted effort from the scientific and tech communities. The currently available technology is not sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 deg C.

The asset manager also said that capital is needed for private companies to scale up existing solutions and serve a broader client base.

For the world to achieve net zero by 2050, investments amounting to US$125 trillion would need to flow into low-carbon energy supply and demand, said the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero.

More public-private partnerships

A common call among observers on what is needed for decarbonisation to take place meaningfully was for more partnerships between the public and private sector.

Accenture’s Lim pointed out that the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) policy report on energy transition in Asean recommends that multi-level, multi-stakeholder dialogues be held, so that governments and companies can have coherent goals at the national and enterprise levels. The goals should also align with all levels of society, from stakeholders to end users.

“Without robust action from the public sector, these companies will be at competitive risk, given the twin burdens of necessary investments and the uncertainty of the pace and scope of technological innovation. Only through working collaboratively can private and public sectors deliver accelerated and value-generating decarbonisation,” he said.

Besides large corporations, public-private partnership also has to include small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), noted PwC’s Fang.

“Governments, larger corporations, and financial services can be helpful by cutting through the complexity and supporting SMEs in a practical way to become more sustainable,” she added.

Besides more public-private partnership, observers say that to accelerate the pace of decarbonisation, there needs to be tighter government regulation around the use of fossil fuels and sustainability reporting standards, as well as a stop in funding for fossil fuels.

DBS noted that some governments in Asia have been showing more interest in decarbonising their carbon emissions as they plan for recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic.

“This top-down focus gives businesses more incentive to reduce their carbon emissions, and over the past couple of years, we have seen more Asian corporates making commitments to move towards net-zero emissions, as well as taking steps to decarbonise and assess the financial and other ramifications of transiting towards a low-carbon economy,” it said.

And developing more robust ESG practices has borne financial benefit for some companies, said DBS Private Bank.

It noted that ESG issues are increasingly impacting financial revenues of businesses. Businesses that play a proactive role in creating positive social impact have stronger financial gains and sustainable long-term growth, affecting investors’ decision-making for their portfolio.

New opportunities and opportunity costs also arise for businesses.

Fang noted that Singapore is a good location for companies to innovate and develop cost-effective decarbonisation solutions, helped by greater international collaboration between governments.

“Companies can take advantage of Singapore’s circumstances and location to aspire to be best-in-class rather than try to conservatively protect margins,” she said.

Liew also noted that companies that decide not to embark on decarbonisation may lose market share if their competitors come up with a greener product with a higher demand among consumers.

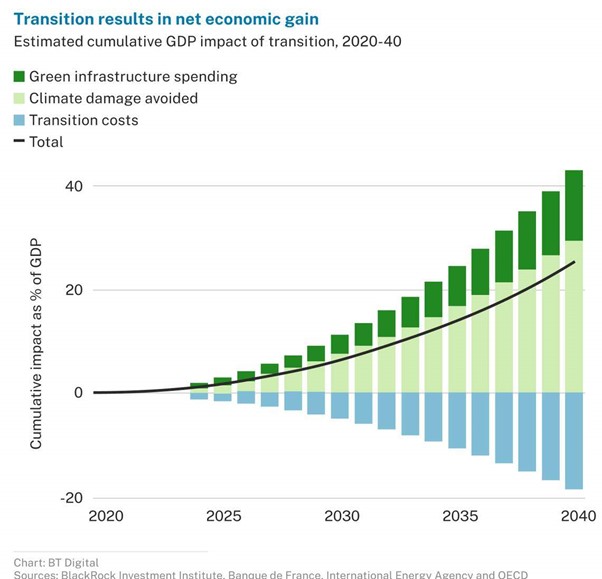

According to data from BlackRock, there would be an estimated 25 per cent global cumulative loss in economic output if no measures to mitigate climate change are taken.

Conversely, an orderly transition should result in a 25 per cent net gain in global growth by 2040.

“People have to understand that achieving net zero in 2050 isn’t something we can start in 2049, and opportunities to participate are already emerging today,” said BlackRock.

But even as the global community attempts to move the needle on decarbonisation, Fang reminded that it is important that entities surround their transition journeys around authenticity.

This includes having a comprehensive measurement of an entity’s carbon emissions and taking a science-based approach towards decarbonisation, such as the Science-Based Targets Initiative.