Find what you need

Learn

Manage your money better with our how-to guides and tips

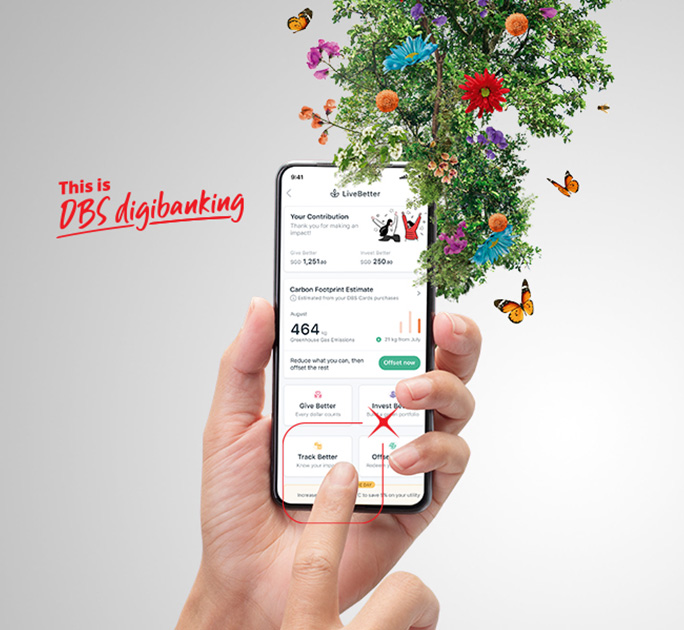

LiveBetter for a sustainable world

Our Green Solutions make it easy and rewarding to go green every day.

Quick Tools

Get the numbers you need here